Why should we care about St. Tammany’s split from Metro New Orleans?

Published: Sep 16, 2024

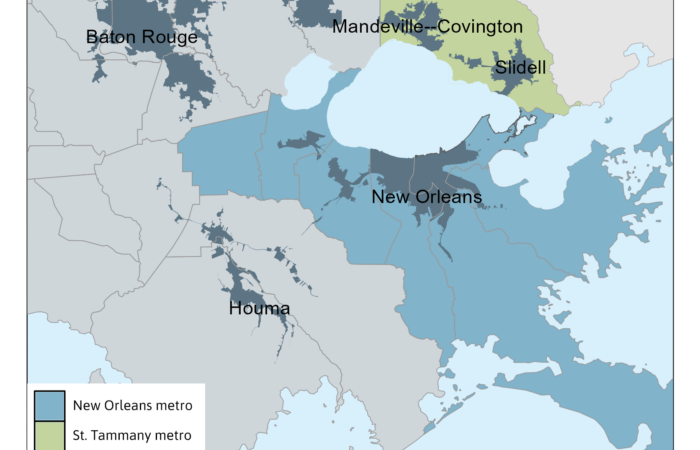

Starting with data released for 2023, the metropolitan statistical area (MSA), anchored by New Orleans — officially, the New Orleans–Metairie MSA — no longer includes St. Tammany Parish. Following a 2020 update published by the federal government and implemented this year, the New Orleans–Metairie MSA now covers seven parishes: Plaquemines, St. Bernard, Orleans, Jefferson, St. Charles, St. John the Baptist, and St. James. Additionally, a new Slidell–Mandeville–Covington MSA has been created, which consists only of St. Tammany Parish.

Why have these official definitions changed? The short answer is that a smaller portion of workers who live in St. Tammany are commuting to work in Orleans, Jefferson, and other parishes on the south shore of Lake Pontchartrain. This smaller portion no longer meets the criteria for St. Tammany to be included in Metro New Orleans. For a longer answer, keep reading below where we run down the details.

As a result of the change, the new official population of Metro New Orleans is lower than you might recall. According to the Census Bureau, the population of Metro New Orleans was 962,165 in 2023. If St. Tammany were included, the population under the old 8-parish definition would be 1,237,748 in 2023. The massive discrepancy between these two numbers is overwhelmingly driven by the official removal of St. Tammany’s resident population from the total rather than by population loss in the individual metro parishes. The bottom line is that, going forward, the official estimate will reflect a 7-parish region of under 1 million, not an 8-parish region of over 1.2 million. Without St. Tammany, basic measures of Metro New Orleans’ demographic and economic makeup will also change.

This change is important for data users to understand. We wrote this research note to explain why the change is happening and what it means. It closes with a few reflections about “regionalism” and the role of data in promoting it.

Why was St. Tammany’s status changed in 2020?

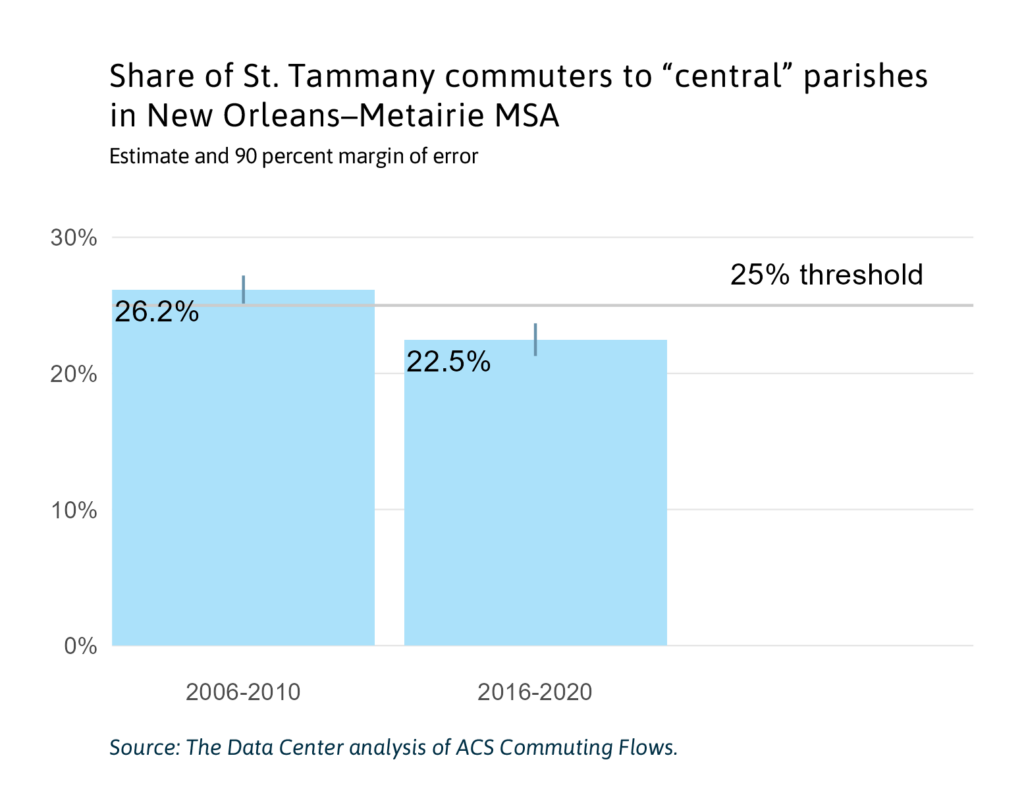

Though it occurred in 2020, the MSA update is going into effect this year first with the release of population estimates for the year 2023 and for other metro-level data releases going forward. Based on Office of Management and Budget (OMB) rules, St. Tammany had previously been classified as an “outlying county” of the New Orleans–Metairie MSA. Its two urban areas around Mandeville–Covington and around Slidell are geographically separate and distinct from the larger urban area on the south shore. Because more than 25 percent of St. Tammany residents who work commuted to the six “central counties” on the south shore, St. Tammany previously met the criteria to be part of the New Orleans–Metairie MSA.

For the last major update in 2010, which used data collected from 2006-2010, 26.2 percent of St. Tammany’s workers were commuting to the south shore. In the new estimates used for OMB’s latest major update in 2020, which use data collected from 2016-2020, this portion had fallen to 22.5 percent. The 25 percent commuting threshold is no longer met. Further, St. Tammany’s two urban areas have sufficient population to define the parish as a “central county” in a new MSA, deemed the Slidell–Mandeville–Covington MSA.

Based on a 5-year sample collected by the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, these estimates have random sampling error. However, the OMB guidelines stipulate the use of point estimates only, and make no attempt to account for sampling error in the underlying data. Nonetheless, even when allowing for a 90 percent confidence interval, to account for sampling error, the current estimate does not meet the 25 percent threshold. In addition, while it may seem possible that the shift to telecommuting in the wake of COVID-19 could have affected the current estimate, the 2016-2020 5-year sample was largely before the height of pandemic lockdown in 2020. Its overlap with the 5-year sample is too small to affect confidence in the result. It also bears noting that different data sources can lead to different results. Data on the commuting patterns of wage-and-salary workers (based on administrative data sources instead of surveys) suggests that around 28-29 percent of workers who live in St. Tammany commute to the “central” parishes in the New Orleans–Metairie MSA.1 However, this is not the official measure used for metro area delineation.

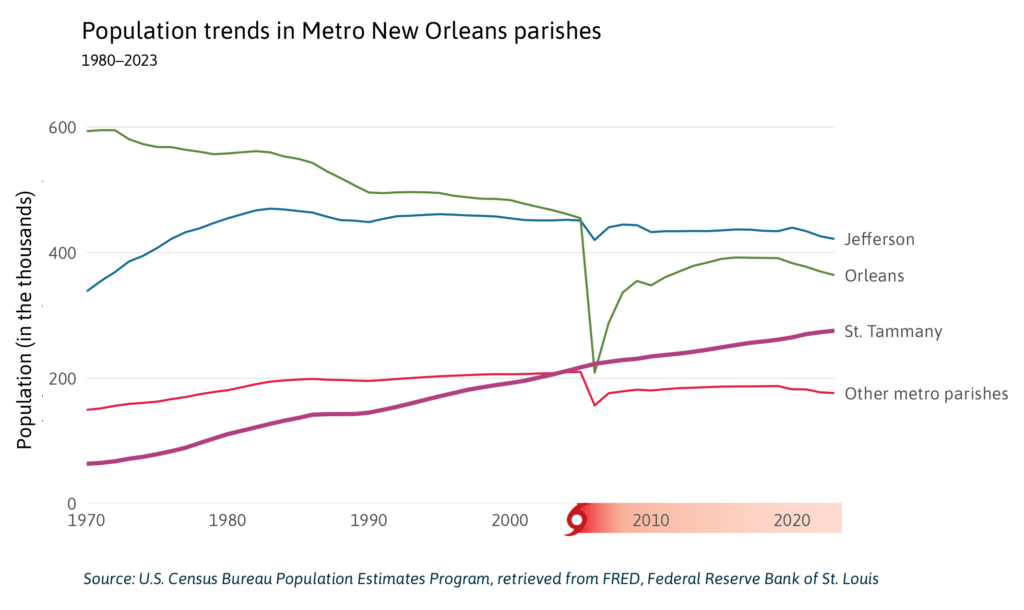

The falling rate of commuting suggests that St. Tammany has become a little less of a “bedroom community” for jobs located in Orleans Parish, Jefferson Parish, and other parts of the south shore. To put this trend in long-term context, setting aside the recovery years after Hurricane Katrina in 2005, most of the population growth in Metro New Orleans since the 1980s has occurred in St. Tammany Parish. The population of St. Tammany has grown at a steady pace from 63,585 in 1970 to 275,583 in 2023. Meanwhile, the population of Orleans Parish has been on a downward trend since the early 1980s, as has Jefferson Parish since 2000.

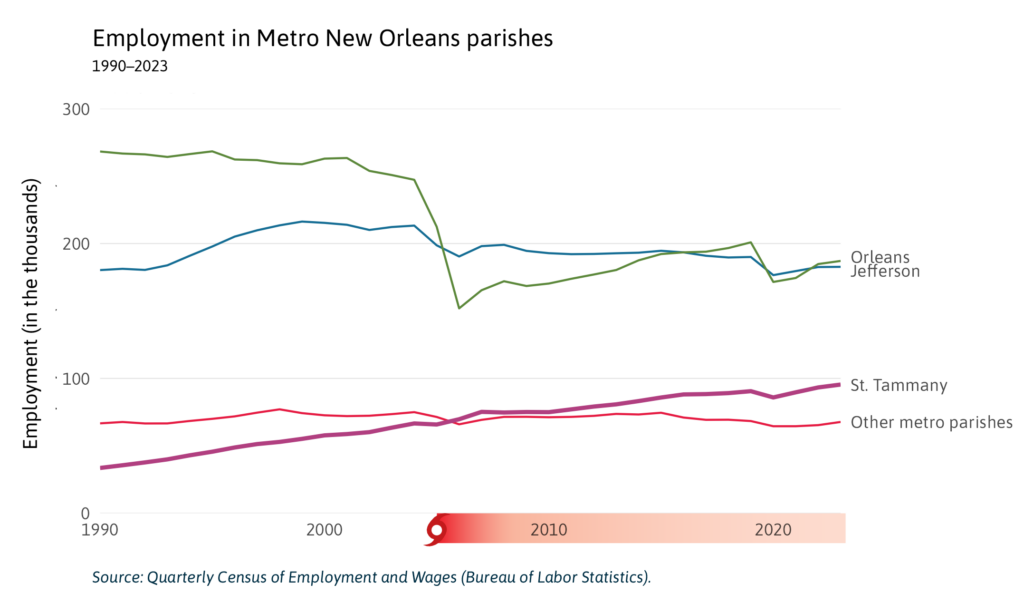

Employment in St. Tammany also has been increasing at a steadier pace than employment in other metro parishes. In 1990, Orleans and Jefferson parishes accounted for over 80 percent of employment, according to the 8-parish MSA definition that included St. Tammany. As of 2023, this share had fallen to 70 percent, with 187,000 jobs in Orleans and 182,000 jobs in Jefferson. Over the same period, St. Tammany’s share grew from 6 percent to 18 percent, as its number of jobs increased from 34,000 to 95,000.

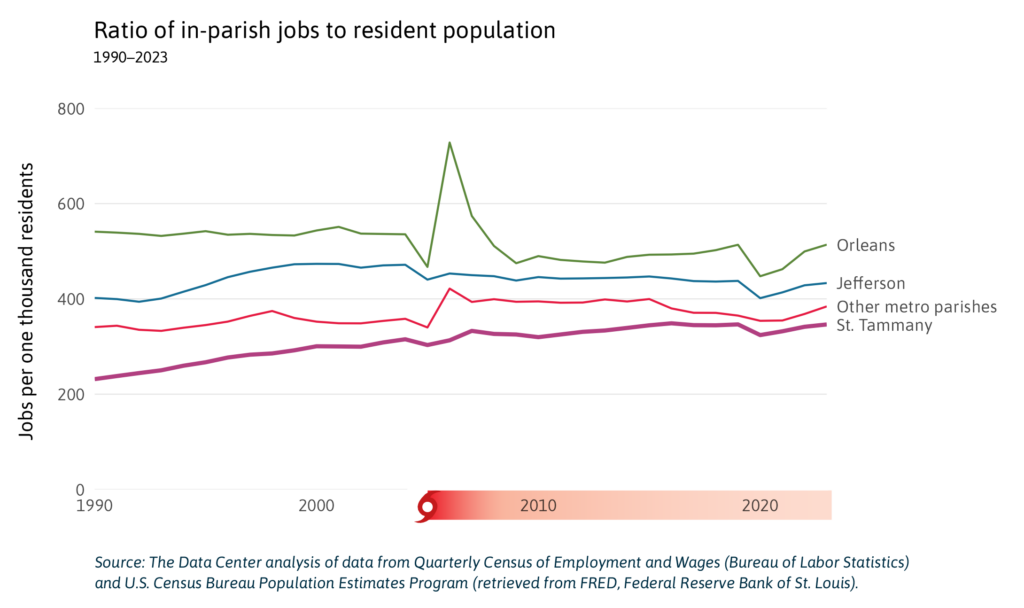

Because St. Tammany’s jobs have grown at an even faster pace than its population, the ratio of jobs to population has increased, from 232 jobs for every 1,000 residents in 1990 to 346 jobs for every 1,000 residents in 2023. The job-population ratio in St. Tammany remains lower than in Orleans and Jefferson (and Plaquemines, St. James, and St. Charles). But unlike in St. Tammany, the jobs-to-population ratio in Orleans and Jefferson is lower than it was during the early 2000s, before Hurricane Katrina. Altogether, these measures track a relative shift in metro area jobs to St. Tammany Parish that has outpaced the shift in population, making it more likely for residents of St. Tammany to find jobs located in St. Tammany.

In summary, the separation of St. Tammany from Metro New Orleans is driven by a change in commuting patterns, a reduction of only a few percentage points. This single data point reflects longer-term trends within the region, chiefly St. Tammany’s growth relative to Orleans and Jefferson. The deeper question involves what this change portends for regional integration.

Are there any real-world consequences to the removal of St. Tammany?

Does having a lower official MSA population have any consequences for local governance or funding? The short answer is: Not really. At least not directly, outside of very specific exceptions. Some official federal population numbers, like the parish-level Population Estimates Program, are used directly for federal funding allocations. MSA populations in most cases do not directly affect federal funding formulas, although they may be used as part of needs assessment. While none of the eight parishes have had changes to their metropolitan/non-metropolitan status, this can affect eligibility for some programs.

One exception where there is a direct impact of MSA redefinition involves complicated reimbursement formulas for health care provided through Medicare. These formulas use a CBSA-level wage index to adjust for differences in regional wages. Assessing the impacts of the MSA redefinition at this level of detail is outside of the scope of this research note.

Unlike parishes and states, MSAs generally do not correspond with governmental jurisdictions. MSAs do not hold a fiscal and regulatory function like local governments, nor do they make or enforce policy. Like many states, Louisiana has quasi-public regional planning commissions, and many state agencies divide the state into regions for the purpose of planning and administering state programs. These administrative regions typically do not align with MSA boundaries. A number of non-governmental organizations located in Metro New Orleans, and pursuing a mission with regional scope, also adopt their own definitions of the region. The MSA redefinition does not directly affect any of these ways that the concept of a region is put into practice for planning or administrative purposes.

Why is the region’s statistical definition important?

While the MSA redefinition may not have immediate consequences for funding or local governance, it forces us to reconsider how we tell stories about our region, which has implications for regional collaboration and problem-solving.

In most cases, regions are a matter of perspective. Unlike municipalities, metropolitan areas have no power to set regulations or enforce laws, leaving regional narratives with an out-sized role in the pursuit of a shared regional agenda. Regions often only become “real” through the stories we tell about them. So, how we tell those stories is critical.

The most consequential stories that make Southeast Louisiana into a cohesive region are rooted in a shared history of cultural, economic, and political relationships — all of which are woven through the range of natural and built environments we associate with the region. These are the stories that shape our understanding of how the region was built as it exists today, about who prospers and why, and about the collective opportunities and challenges we face. However, we also use tools like the official MSA boundaries to organize stories we tell with data. These include stories about the size and composition of the region as a functional demographic and economic unit and stories about regional integration and equitable prosperity.

As a result of the MSA redefinition, Metro New Orleans no longer makes the cut for metros with a population greater than one million. We remain the second smallest metro to host an NFL team; but now, we join Green Bay as the only NFL host metro that does not eclipse one million residents. Likewise, St. Tammany is no longer a booming suburb but a small metro. Naively looking at these two MSAs, neither is as large or economically diverse on paper as it was before. While these “on paper” changes are distorted by the separation of St. Tammany into its own metro, the risk lies in the fact that naive data analysis is very common. For example, market analysts scanning national data for locations to make an investment might now fail to find a sufficient customer market or workforce when looking at metro-level data. Arguably, ranking metros has become something like a cottage industry, one that often converts thin data analysis into click bait. Savvy data users will recognize how removing St. Tammany, which was one fifth of the metro population, will affect static rankings and will put a kink in dynamic trends used to track prosperity and change in the region. The redefinition not only alters the statistical picture but also disrupts the narrative of a unified Southeast Louisiana region.

The MSA redefinition creates a statistical division where none existed before, making it just a little bit harder to bring data to bear on a shared story about the north and south shores — a story about regionalism. Regionalism is a perspective that recognizes the interconnected, cross-jurisdictional nature of many local challenges and elevates the shared fates of a region’s constituent localities and communities. Due to the lack of regional governance structures in the United States and the dependence of many public functions on local taxes, local jurisdictions often pursue their own fiscal and development priorities, sometimes at the expense of their neighbors. From one view, this can be justified as an expression of local control. From another, a lack of regional coordination leads to zero-sum competition, increases the costly inefficiencies of governmental fragmentation, and factionalizes decisionmaking on issues that transcend local jurisdictional boundaries. Many of the most universal and critical local issues — economic development, housing, transportation, and environmental management — are in fact regional issues. Further, regionalism recognizes that the modern economy is an economy of regions, and only by maximizing regional potential can local governments ensure their position in a changing national and global landscape.

The late decades of the 20th century saw deepening gaps in prosperity both within and across regions in the U.S. Since then, civic and policy leaders, domain experts, and academics have frequently sought to promote regionalist alternatives2. The Data Center’s mission is fundamentally regionalist, and the pursuit of equitable regional prosperity partly drives our work. We routinely publish data and analysis on the metro parishes and the metro economy, and we have published essays on wealth in Metro New Orleans, Black political power in New Orleans through a regional lens, and regional economic integration, to give just a few examples. A regionalist vision is shared by numerous nonprofit and government leaders. Many of Southeast Louisiana’s deepest economic and environmental challenges, like the energy transition and the coastal crisis, are also inescapably regional.

Regionalism and Louisiana’s coastal crisis

Tropical weather, severe floods, and coastal ecosystems do not care about city and parish boundaries. This makes adapting to south Louisiana’s coastal future a fundamentally regional project. Regional cooperation and management are traced through numerous coastal and flood initiatives in Louisiana and are critical to their success. The whole “Coastal Zone” from Plaquemines to Lake Charles area has been the focus of Louisiana’s massive investment in coastal flood protection and ecosystem restoration through the Coastal Master Plan. In fact, the Mid Barataria Sediment Diversion, a lynch-pin coastal project with broad regional implications, has continued to experience delays due to disagreement on local benefit.

After the 2016 floods, the Louisiana Watershed Initiative attempted to transform regional watershed planning across the entire state. The scale of investment also creates regional economic opportunities. In The Coastal Index and other reports, The Data Center has explored the Southeast Louisiana “super-region” and its interconnected economy of coastal adaptation. Despite their distance and distinctiveness, the New Orleans, Baton Rouge, and Houma–Thibodaux regions share not only environmental vulnerability but also critical economic linkages and capacities for innovating on coastal protection and adaptation.

Despite its importance, regionalism is not without its challenges. High-minded appeals for regionalism often struggle against the strong forces of racial segregation, place-based inequality, and local fiscal constraints; and a regionalist perspective can leave struggling inner city and rural communities on the metropolitan fringe with a diminished role in their own uncertain futures. Some regions in the U.S. have pursued reforms to restructure local government to give more weight to regionalism, albeit with varying levels of success. Counter-examples also exist. One could view the incorporation of St. George in East Baton Rouge Parish — upheld by the state supreme court earlier in 2024, creating the fifth largest municipality in the state — as arguably working against the principles championed by regionalism.3

One way or the other, it’s difficult to have a realistic conversation about building a more equitable, prosperous, and environmentally sustainable future in Southeast Louisiana without also telling a story about regionalism. Carving St. Tammany from Metro New Orleans won’t affect our daily lives or our biggest policy decisions, but it changes the way we tell data-driven stories about the region. Such stories have a vital role to play in shaping our regional future, and they just became a little harder to tell.

Endnotes

1Based on an analysis by The Data Center of data from the Census Bureau’s Longitudinal Employer-Household Dynamics program.

2Dreier, Peter, John Mollenkopf, and Todd Swanstrom, Place Matters: Metropolitics for the Twenty-First Century. Revised. (University Press of Kansas, 2014)

3Rick Rojas, “Louisiana Will Get a New City After a Yearslong Court Battle,” The New York Times, April 28, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/28/us/louisiana-st-george.html

Sources and References

Office of Management and Budget. 2021. “2020 Standards for Delineating Core Based Statistical Areas.” https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/07/16/2021-15159/2020-standards-for-delineating-core-based-statistical-areas.

“OMB BULLETIN NO. 23-01.” Executive Office of the President. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/OMB-Bulletin-23-01.pdf.