COVID-19 Economic Analysis

Robert Habans

First Published: Mar 27, 2020

Updated: Jul 21, 2020

This webpage highlights data relevant to the effects of COVID-19 on the local economy. Indicators include initial unemployment claims for Louisiana and workers who might be at most immediate risk of job loss. While we won’t know the full effects of this unprecedented public health and economic crisis for some time, we will continue to publish indicators here about how our region’s workers and businesses might be affected to inform decisionmakers about the ripple effects of COVID-19 on our local economy.

Unemployment insurance claims

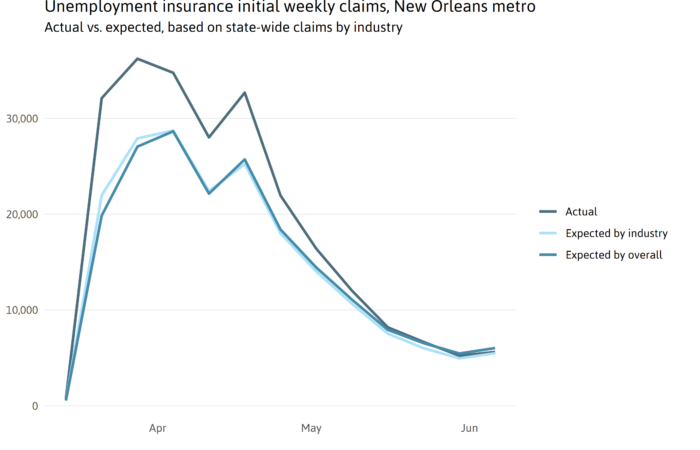

The COVID-19 crisis is causing unprecedented disruptions to the economy, both locally and nationally.1 We should learn more about the effects on our local economy over the coming months. In the meantime, initial unemployment insurance (UI) claims in Louisiana show how many newly unemployed workers have applied for benefits.2 Initial claims don’t reflect a comprehensive count of joblessness, but they do offer a nearly up-to-date gauge for how many individuals are experiencing separation from employment and then applying for benefits on a week-by-week basis.

Sources:

Note: Claims for the most recent week is an advance figure that is not directly comparable to claims reported in previous weeks and is subject to revision.

Nationally, UI claims have already shattered the previous record.3 In Louisiana, the only recent precedent for COVID-19’s effect on UI claims occurred in the weeks after Hurricane Katrina. Weekly employment losses have already far surpassed the peak of the Great Recession.

Sources:

Notes: Claims for the most recent week is an advance figure that is not directly comparable to claims reported in previous weeks and is subject to revision.

Unemployment insurance is a joint state-federal program that provides temporary income to workers during spells of unemployment. Due to exclusions and limits, this temporary income normally only partially compensates jobless workers for lost earnings. Typically, eligible workers receive temporary cash benefits to replace part of their wages for up to 26 weeks.4 Louisiana is also one of only six states with a maximum weekly benefit below $300.5 Unemployment insurance typically doesn’t cover workers who don’t receive a W-2, like freelancers, gig workers, musicians, and some part-time workers. Women and people of color are more likely to fall through the cracks.6

The UI system will serve a critical role in how workers cope with the impacts of COVID-19. UI benefits play a critical role in the labor market, especially in times of economic distress when it can help to boost spending.7 The federal CARES Act relief package will temporarily increase UI benefits by $600 per week and extend eligibility to cover more workers who are not normally eligible.8

Initial unemployment claims by industry

The Louisiana Workforce Commission has made additional data on new UI claims available by industry sector and parish.9 We pooled together the first three weeks of the COVID-19 spike (for the weeks ending in March 21, March 28, and April 4) to give a more detailed look at the early effects of COVID-19 on different parts of the economy. As many have expected, the data shows that the biggest spike occurred in the Accommodation and Food Services sector, with a weekly average of nearly 24,000 new claims over the three weeks included in the analysis.

To provide a common reference point for sectors with different employment levels, initial claims can be compared with the most recent available UI-based employment data from September 2019.10 Over the three weeks included in the analysis, the Louisiana Workforce Commission received one or more new claims for every three UI-eligible employees in three sectors: Accommodation and Food Services; Arts, Entertainment, and Recreation; and “Other Services.”11

In the 8-parish New Orleans metro area, initial UI claims over the first three weeks of the post-COVID-19 spike add up to nearly 105,000. This is comparable to 19 percent of total employment covered by unemployment insurance in 2019.12 While initial claims are a crude measure for joblessness, these numbers help to illustrate the scale of COVID-19’s impact on the workforce.

Preliminary look at which workers might be most at-risk of job loss

Detailed employment data arrives slowly,13 so the picture of how COVID-19 is affecting our economy will grow clearer as updated data is released. Until then, prior data can provide clues into which parts of the economy might be most vulnerable. Several national and local analysts have offered back-of-the-envelope estimates of the number of workers at the most immediate risk of job loss, temporary furlough, or hours reduction.14 We’ve rounded up a few of these analyses, extended them, and highlighted data relevant to our region. At present, the analysis focuses on immediate job loss risks rather than continued health risks to workers, impacts on small businesses and the public sector, or any of the possible longer-term economic ripple effects of COVID-19. The Data Center will refine and extend the analysis as we learn more and as more data on the economy after COVID-19 becomes available.

Below, we present an industry approach and an occupation approach, both based on assumptions about how social distancing, travel restriction, and other public- and private-sector measures to slow the spread of coronavirus may disrupt some kinds of work more than others. To be clear, risk of job loss does not mean that every worker in these occupations and industries has experienced or will experience job loss. Nor does it mean that other sectors will be entirely spared. These are rough but expert- and data-driven approximations based on comparing work that is essential or can be accomplished from home with work that is not – including restaurants, hotels, retail, and personal care.

Estimates differ, but a few key takeaways are consistent:

- Impacts will be widespread but concentrated in certain sectors of the economy.

- Many of the workers most at risk may be the least equipped to weather an income shock or employment disruption.

- The New Orleans metro may face more risk than other metros due to the composition of its economy.

Industries versus occupations: Industries are types of business establishments that produce similar or related products or services. Hospitals, hotels, gas stations, and grocery stores are industries. Occupations are types of positions or professions defined by specific tasks or skills. Architects, economists, musicians, and cashiers are occupations. In general terms, data on industries more closely reflects how an economy is structured, and data on occupations more closely reflects the skills, working conditions, and quality of jobs.

Risk of job loss by industry

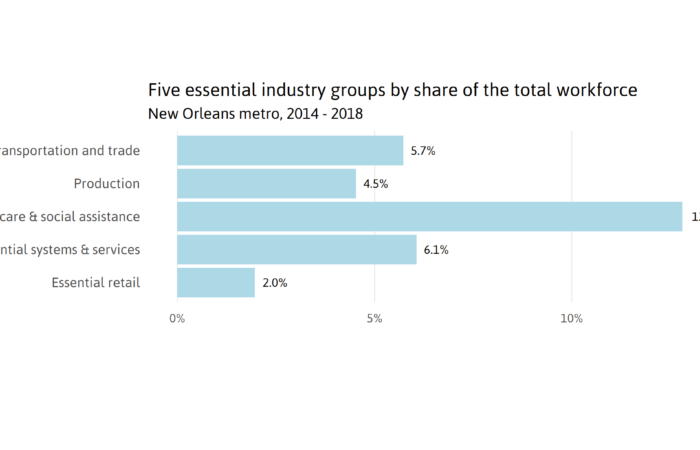

Brookings recently published metro-level data on industries at “immediate risk” of employment disruption due to COVID-19.15 Using 2018 data, they found that immediate-risk industries employed 37 million people, 23 percent of the US workforce. Other approaches using different methods have arrived at similarly large estimates.16

For the New Orleans metro, 172,000 workers are in immediate-risk industries as defined by Brookings, making up 30 percent of the total workforce.17 The industry sectors with the largest risk of job loss are Retail and Food Services and Drinking Places, which account for about 19 percent of jobs in the region. Food Services and Drinking Places and Accommodation include most of the jobs driven directly by tourism spending and make up a relatively large portion of the workforce in the region and especially in the city of New Orleans. According to a 2017-2018 national survey, only 9 percent of leisure and hospitality workers reported that they could work at home, the lowest of any industry sector. In contrast, one-quarter of all workers and over one-half of some predominately white-collar sectors reported that they could work from home.

Sources:

- Immediate risk sectors: Berube, Alan and Nicole Bateman. (2020). “Who are the workers already impacted by the COVID-19 recession?” Brookings.

- Employment: The Data Center analysis of data from EMSI. Brookings originally used ACS microdata to estimate employment, and these EMSI-derived estimates differ slightly. Note that employment by sector is not necessarily the total employment in the sector but only the portion of each sector that is in immediate-risk industries. For example, the Retail sector excludes the Pharmacy and Grocery Store industries.

Given the sizeable role of tourism and oil and gas in our region relative to other regional economies, Brookings’ analysis suggests that the New Orleans metro economy may face steeper job losses than other large metros. Among metros with population over 1 million, only three had a higher share of employment in “immediate-risk” industries: Las Vegas, Orlando, and Oklahoma City.

Sources:

- Berube, Alan and Nicole Bateman. (2020). “Who are the workers already impacted by the COVID-19 recession?” Brookings. To

develop their estimates, Brookings used a 1-year sample of 2018 ACS microdata of 1,661 immediate-risk workers and

4,553 other workers.

- Metro populations: American Community Survey 1-year estimates for 2018.

The Brookings analysis also sheds light on the characteristics of vulnerable workers. Workers in “immediate-risk” industries earn lower wages and salaries and have lower family incomes than workers in other industries with less immediate risk. They are also more likely to be renters, more likely to live in households below 200 percent of the federal poverty level, less likely to have completed a four-year degree, and less likely to work on a full-time and year-round basis. The vulnerable industries are more than twice as likely to employ young workers (age 18-24). Black workers and women are also overrepresented in vulnerable industries.

Risk of job loss by occupation

The St. Louis Federal Reserve published an occupation-based estimate of employment at high risk of layoff.18 Occupations essential to public health and safety, likely capable of completing work off-site or at home, or likely to be salaried were deemed “low risk” for job loss. With all other occupations deemed “high risk,” this approach led to an even greater estimate of 67 million jobs at risk nationally or 46 percent of the national workforce.

For greater New Orleans, essential occupations accounted for about 18 percent of employment, and working from home is likely possible for 27 percent of employment. High-risk occupations encompass 49 percent of the regional workforce.19 While a diverse range of occupations are at risk, many are related to sales and the preparation and serving of food.

Echoing the finding of the industry-driven analysis published by Brookings, the share of employment in high-risk occupations in the New Orleans metro ranked near the top among large metros.

The occupation-based estimate also suggests that the most at-risk occupations tend to be lower earning. The scatterplot shows different hourly earnings levels (median wages or hourly salary equivalents) for broad groups of occupations. Each occupation group is colored by the share of its employment that is classified as high-risk in the St. Louis Fed analysis. The occupation groups with the most extensive risk of job loss tend to include lower-earning jobs, and lower-paid occupations are less amenable to home-based work.20 Sales, Food Preparation and Serving, Personal Care and Building and Grounds Maintenance Occupations are low-wage occupations that may be particularly vulnerable to the combination of limited financial resources and the most immediate threat of job loss.

Speculative, back-of-the-envelope estimates suggest that the risk of job loss is distributed unevenly to lower-earning workers. The shock of job loss can acutely undermine the ability of families with limited liquid assets to afford basic expenses and debt payments, especially when experiencing prolonged unemployment.21 The estimates reported above expose how precarious finances and well-being could become for workers who may lose jobs and who likely already have lower earnings. The New Orleans metro’s relatively large share of at-risk industries and occupations also points to the potential ripple effects on the regional economy of a prolonged contraction of spending by unemployed workers. During the public health fight against COVID-19, a major benchmark for economic policy responses will be to maintain the well-being of displaced workers. The employer payroll, unemployment insurance, and direct relief payment provisions of the CARES Act should alleviate some of the current and impending hardships, but further steps at the state and local level might be necessary, both as a short-term “bridge,” where support is late or insufficient, and in the longer-term transition to more resilient employment opportunities for vulnerable workers.22

1 Nationally, during the week ending in March 14, initial unemployment insurance claims jumped from 211,000 to 282,000. The next week, initial claims soared to nearly 3.3 million, shattering the previous record.

2 Advance claims are from the U.S. Department of Labor. This week’s UI claims were not available from the Louisiana Workforce Commission at the time of writing. Advance claims may differ slightly.

3 Nationally, during the week ending in March 14, initial unemployment insurance claims jumped from 211,000 to 282,000. The next week, initial claims soared to nearly 3.3 million, shattering the previous record.

4 To continue collecting benefits for the full 26 weeks of eligibility, individuals must be able, available, and actively seeking to work.

5 U.S. Department of Labor Employment and Training Administration. (2019). “Chapter 3 Monetary Entitlement” in Comparison of State Unemployment Laws 2019. https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/comparison/2010-2019/comparison2019.asp

6 Less than 20 percent of jobless workers receive unemployment benefits in our state, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. See Leachman, M. and Sullivan, J. (2020). “Some States Much Better Prepared Than Others for Recession.” Center on Budget and Priorities. https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/some-states-much-better-prepared-than-others-for-recession/; Women’s Law Center, National Employment Law Project, Economic Policy Institute, the Century Foundation, Georgetown Law Center on Poverty and Inequality Economic Security of Opportunity Initiative. (2020). "Fact-sheet: Fixing Unemployment Insurance in Response to COVID-19." https://www.georgetownpoverty.org/issues/fixing-unemployment-insurance-in-response-to-covid-19/.

7 Rothstein, J. and Valetta, R.G. (2017). “Scraping by: Income and program participation after the loss of extended unemployment benefits.” Washington Center for Equitable Growth Working Paper Series. https://equitablegrowth.org/working-papers/income-after-loss-of-extended-unemployment-benefits/; Chikhale, N. (2017). “The importance of unemployment benefits for protecting against income drops.” Washington Center for Equitable Growth. https://equitablegrowth.org/the-importance-of-unemployment-benefits-for-protecting-against-income-drops/

8 Bridges, Tyler. (2020). “See big questions, answers for Louisiana $600 coronavirus unemployment boost.” Nola.com

9 The Louisiana Workforce Commission data is published as a Tableau dashboard and as a spreadsheet in an April 9th press release.

10 This data comes from the federal Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages, which includes all workers covered by state unemployment insurance laws, as well as some federal workers. This data covers 95 percent of jobs nationally and provides the most appropriate reference point for UI initial claims.

11 According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Other Services” includes businesses primarily engaged in a wide range of activities: “equipment and machinery repairing, promoting or administering religious activities, grantmaking, advocacy, and providing drycleaning and laundry services, personal care services, death care services, pet care services, photofinishing services, temporary parking services, and dating services.” See Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2020). “Industries at a Glance: Other Services (except Public Administration): NAICS 81.”

12 Detailed industry data is not available by parish or metro.

13 McCracken, Michael. (2020). “COVID-19: Forecasting with Slow and Fast Data.” St. Louis Fed: On the Economy Blog. https://www.stlouisfed.org/on-the-economy/2020/april/covid-19-forecasting-slow-fast-data; Bureau of Labor Statistics Release Calendar. https://www.bls.gov/schedule/

14 These analyses focus on estimating immediate economic and job loss risks due to the broad economic shutdown of non-essential industries and stay at home orders, not the types of risks that frontline and essential employees experience as they keep going to work. Upcoming analysis will focus on this group and their vulnerabilities.

15 Berube, Alan and Nicole Bateman. (2020). “Who are the workers already impacted by the COVID-19 recession?” Brookings.

16 The Job Quality Index team at Cornell University took similar approach with a different but overlapping set of industry categories. According to their national estimates, these industries employ 37 million production and non-supervisory workers who are vulnerable to layoff in the short-term. See “Statement from the U.S. Private Sector Job Quality Index (“JQI”) Team on Vulnerabilities of Jobs in Certain Sectors to the Covid-19 Economic Shutdown." Pew Research Center arrived at a similar number of 38.1 million. See “Young workers likely to be hard hit as COVID-19 strikes a blow to restaurants and other service sector jobs.”

17 These number differ slightly different from Brookings’ estimate. Our analysis applies Brookings’ industry definitions to a different source, EMSI data for 2019. Brookings’s estimates use ACS microdata for 2018.

18 Gascon, Charles. (2020). “COVID-19: Which Workers Face the Highest Unemployment Risk?” On the Economy Blog. The St. Louis Federal Reserve.; Gascon, Charles. (2020). “COVID-19 and Unemployment Risk: State and MSA Differences” On the Economy Blog. The St. Louis Federal Reserve.

19 The Data Center replicated the St. Louis Fed analysis with EMSI data instead of the original’s use of Occupational Employment Statistics. Both resulted in an estimate of 48.7 percent.

20 Avdiu, Besart and Gaurav Nayyar. (2020). “When face-to-face interactions become an occupational hazard: Jobs in the time of COVID-19”. Brookings.

21 Farrell, Diana, Fiona Grieg, and Chris Wheat. (2020). “The potential economic impacts of COVID-19 on families, small businesses, and communities: Insights from five years of big data research.” JPMorgan Chase & Co. Institute.

22 Berube, Alan and Nicole Bateman. (2020). “Who are the workers already impacted by the COVID-19 recession?” Brookings.

More